Sponsored Content by HORIBAReviewed by Olivia FrostJan 14 2026

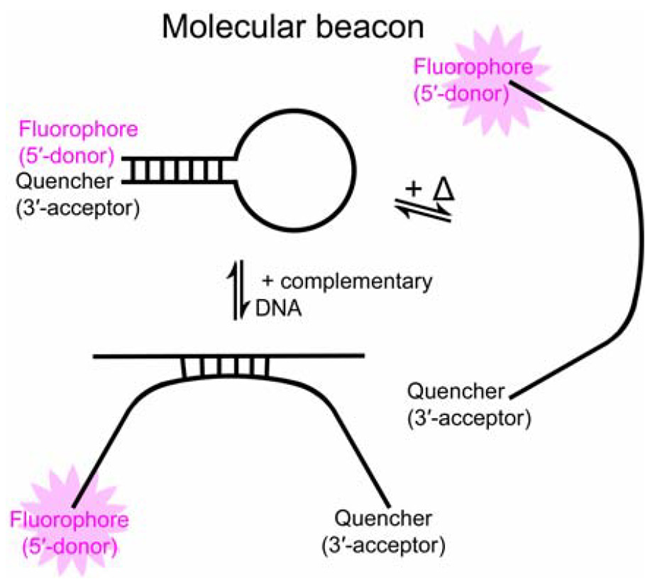

Gene expression studies can monitor biological processes using a “molecular beacon” (single-stranded DNA, ssDNA), a hairpin-shaped oligonucleotide containing a fluorophore (donor) and a quencher (acceptor). The stem of the hairpin includes two ends of complementary DNA (cDNA) that pair up.

Upon hybridization, the fluorophore and quencher are in close proximity, resulting in minimal or no fluorescence. Molecular beacons are employed to investigate enzyme interactions, cDNA sequencing, and biosensing.1 These beacons demonstrate two types of quenching (energy-transfer): direct and Förster resonance energy-transfer (FRET).

Direct energy-transfer is caused by donor-quencher contact, which dissipates heat energy. Across extended distances (2–10 nm, 20–100 Å), spectral overlap between the donor’s emission and the quencher’s absorption leads to FRET.2

When the ssDNA loop encounters cDNA, the hairpin opens spontaneously and the ssDNA hybridizes to the cDNA - separating fluorophore and quencher - and increasing fluorescence (Figure 1). Fluorescence intensity is related to the degree of hybridization. Heat can also open ssDNA. Upon heating, the ssDNA’s arms separate, increasing the distance between donor and acceptor ends and resulting in fluorescence.

Hybridization experiments

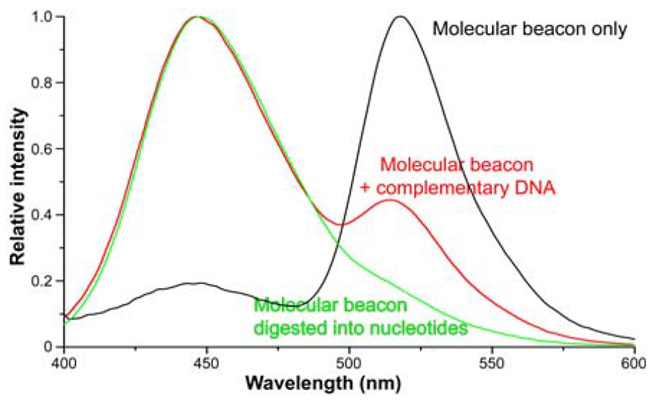

A two-fluorophore molecular beacon was utilized: the donor end was coumarin (λexc = 348 nm; λem = 447 nm), and the acceptor end was 6-carboxy-fluorescein (6-FAM, λem = 518 nm). Emission scans of 100 pM ssDNA alone were recorded using a Fluorolog® spectrofluorometer. 500 nM cDNA was introduced to a 100 nM ssDNA solution, and the spectrum was recorded. Finally, deoxyribonuclease I hydrolyzed the molecular beacon, and another spectrum was acquired (Figure 2).

Fig. 1. Two processes that open a molecular beacon, enhancing fluorescence: (left) hybridization with cDNA; (right) heat input. Image Credit: HORIBA

The donor (Figure 2), positioned near the quencher when the molecular beacon is intact, fluoresces weakly. The donor emits a stronger signal upon hybridization of ssDNA with cDNA, indicating an increased distance from the quencher. When the molecular beacon is hydrolyzed, the distance between the donor and quencher in solution is large enough that FRET ceases, resulting in strong donor fluorescence.

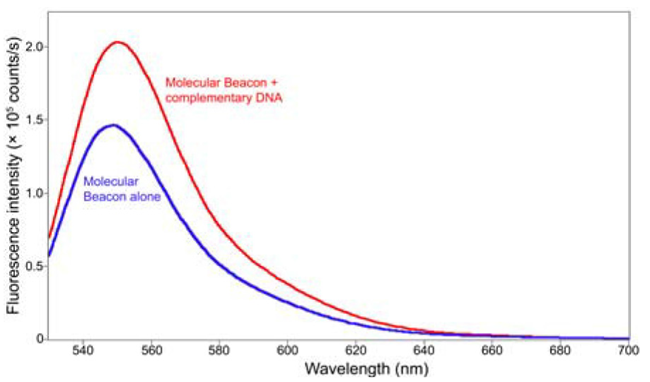

An additional ssDNA hybridization study utilized rhodamine 6G (λexc = 527 nm; λem = 560 nm) as the fluorophore, and non-fluorescent 4-(dimethylaminoazo) benzene-4-carboxylic acid as the quencher. An emission spectrum (Figure 3; integration time = 0.5 s, λexc = 525 nm, slits = 3 nm bandpass) demonstrates that the rhodamine 6G’s fluorescence increases when ssDNA pairs with cDNA. Hybridization opens the ssDNA, separating the fluorophore from the quencher and enabling the fluorophore to fluoresce more intensely.

Fig. 2. Emission spectra (λexc = 350 nm) of: (black) 100 pM ssDNA only; (red) 100 nM ssDNA hybridized with 500 nM cDNA; and (green) ssDNA hydrolyzed by deoxyribonuclease I. Spectra are normalized to the fluorophore λem (447 nm). The 447-nm peak’s height increases relative to the 518 nm quencher peak as fluorophore and quencher separate. Data

from Dr. Weihong Tan, University of Florida. Image Credit: HORIBA

Fig. 3. Comparison of emission spectra between (blue) ssDNA only; (red) ssDNA hybridized with cDNA. The peak’s relative height increases as fluorophor separates from the quencher. Image Credit: HORIBA

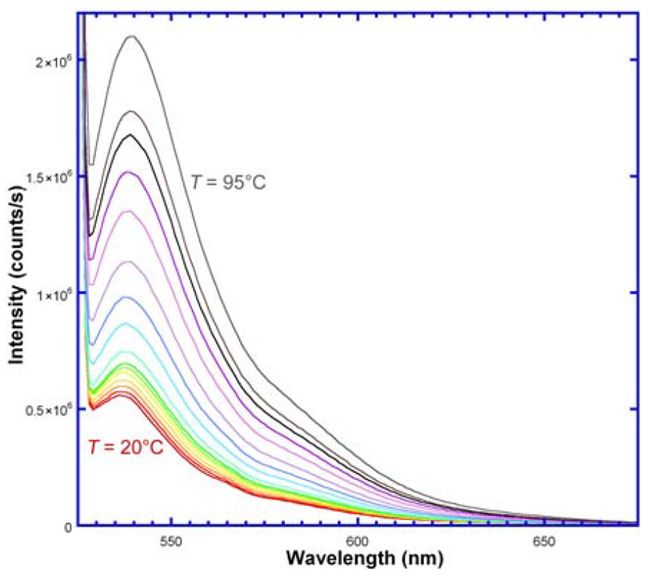

Fig. 4. Emission spectra of ssDNA with TET (fluorophore) and QSY (acceptor); λexc = 521 nm. With rising temperature, fluorescence intensity rises, meaning greater distance between donor and quencher. Image Credit: HORIBA

Annealing experiment

A fluorescent dye (tetrachloro-6-carboxyfluorescein, TET; λem = 447 nm) was attached to a 5’-end of ssDNA, and a quencher (QSY) was bound to the 3’-end. The ssDNA was excited at 521 nm using a FluoroMax®-4 spectrofluorometer. Emission spectra (Figure 4) were recorded from 525–675 nm over a temperature range of 20–95°C. As the temperature rises - forcing the hairpin’s arms apart - the TET and QSY separate, increasing fluorescence.

Conclusions

Fluorescence measurements utilizing HORIBA spectrofluorometers provide a sensitive method for examining biochemical interactions, such as those involving molecular beacons and DNA.

References and further reading:

- Tian, H., Hühmer, A.F. and Landers, J.P. (2000). Evaluation of silica resins for direct and efficient extraction of DNA from complex biological matrices in a miniaturized format. Analytical Biochemistry, (online) 283(2), pp.175–191. https://doi.org/10.1006/abio.2000.4577.

- Fang, X., et al. (2000). Peer Reviewed: Molecular Beacons: Novel Fluorescent Probes. Analytical Chemistry, 72(23), pp.747 A-753 A. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac003001i.

About HORIBA

Founded in 1953, HORIBA has explored a wide range of unique measurement and analysis technologies to meet global customer needs from 47 group companies and local sites spread across 28 countries and regions. Under the corporate motto Joy and Fun, the company has expanded and refined its core tech-nologies to solve society’s energy issues of today and tomorrow. Our unique measurement and analysis technologies are valued in various fields of society including the three megatrend business fields of Ener-gy & Environment, Biology & Healthcare and Materials & Semiconductor. For more information on HORIBA, visit https://www.horiba.com/int/company/about-horiba/home/

Sponsored Content Policy: News-Medical.net publishes articles and related content that may be derived from sources where we have existing commercial relationships, provided such content adds value to the core editorial ethos of News-Medical.Net which is to educate and inform site visitors interested in medical research, science, medical devices and treatments.